Delita Martin was born in Conroe, Texas and earned her BFA in Drawing from Texas Southern University and her MFA in Printmaking from Purdue University. She was formerly a member of the Visual Arts faculty at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock but left with the support of her husband to create her own studio, Black Box Press Studio, and create art full time. Having exhibited her work both nationally and internationally, Delita Martin is in the prime of her career. In Martin’s studio, strange and supernatural things happen. She has a unique approach to portraiture as she aims for portraits to feel like a particular person rather than look like a particular person. To conjure is to make something appear (or seem to appear) through mysterious magical means. Conjure displays the way that Martin brings to life the essences of the divine women that she puts on the canvas. These massive prints pose questions about magic, identity, spirituality, and the nature of conjuring. According to Martin herself, museum goers leave this sacred space wondering “Are you the viewer or are you now being viewed?”

Conjure—Delita Martin is a collection of spiritual portraits of Black women as Martin imagines their essences filtering in and out of the physical and spiritual realms. The exhibition includes ten monoprints that draw from spiritual and oral storytelling to cultivate a visual language that is unique to Martin. Various shapes and patterns contribute to what Martin calls the “veilscape,” which represent the visual side of the spiritual world. The spiritual world is often represented by the color blue as Martin associates spirituality with nighttime, since it is the time that mothers pray for their children. Martin’s love for blue goes so deep that she often uses indigo blue instead of black to darken colors. Her conception of blue is evident in Offerings, where the veilscape is filled with varying shades of blue. This print also illustrates another common theme in the veilscape: the use of circles. Martin uses circles to represent women because the moon is often a feminine symbol in African cultures. The woman also sits atop a stool, which Martin often uses to convey leadership on her subjects. With the use of circles in the veilscape, combined with the strategic use of blue, Martin is pulling out all the stops in the presentation of divine femininity.

Martin’s primary inspiration in building this world trace back to her relationship with her grandmother, Texanna Williams. While Williams influenced Martin’s art in more practical ways, such as the fact that she taught her to quilt and Martin now incorporates stitching into her portraits, Williams’ spiritual practice heavily inspired the themes behind Martin’s work. Upon considering some of her grandmother’s consistent activities, like using garden herbs to make medicine and interpreting dreams, Martin realized that Williams had been preserving aspects of her African heritage within her practice of Christianity. These realizations about her own spiritual background gave Martin the desire to explore the space between someone’s physical and spiritual self.

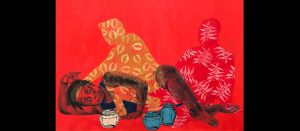

Another facet of Williams’ spiritual practice that influenced Martin’s work was a collection of mason jars that Williams used to hold sacred treasures. Williams shared the contents of these jars with Martin, telling stories of the people, places, and things that she associated with each object contained in the jars. As Martin began to research Williams’ spiritual practices, she came across a concept called “Conjure Bottles,” which were originally used by Afro-American conjurers that were assembled to conjure or protect from conjure. These sacred jars and their conjuring powers have followed Martin into her work. In the monoprint Among Shadows, a woman lies down alongside two shadows that contribute to the chilling veilscape and beside the woman are three open jars. Despite the alarming nature of the atmosphere of the monoprint with the red background and shadowy figures, the woman looks noticeably calm. This comfort suggests that the woman might have used the jars to conjure this spiritual aid.

During Martin’s research into African spiritual practices, she discovered the Sande society, which was a secret group for Mende women living in Sierra Leone and Liberia. This discovery prompted Martin to consider all of the religious and cultural rituals that ushered her into womanhood, inspiring the society of women represented in this exhibition. The Sande are also known for their unique wooden masks designed specifically for women, which Martin references in her portraits. This is true of the print Spirit and Self. Within Mende cultural practices, masks represent the two-fold human experience: one of the concrete physical world and the other of the aspirational spiritual world. Through using the mask, she is suggesting that the masked woman is actively transitioning between the two worlds. The mask makes the figure a sort of consort of spirits, as Martin and the mask both serve as the facilitators of this bridge between the physical and spiritual world.

Martin always knew that she wanted to be an artist. She decided that this was the path for her when she was five, and her parents were always supportive. When she was twelve, her dad took her as she toted some of her drawings to meet internationally recognized artist John Biggers, who gave her her first critique. Biggers became prominent following the Harlem Renaissance and created works inspired by African practices that drew attention to racial and economic injustices. Upon visiting the printmaking studio that Biggers worked in, Martin was entranced by how the complicated process that used so many different chemicals and materials could yield something so simple and beautiful. She also loved the collaborative movement that printmaking inspired, saying that it was like a magical dance for all involved. Her experience this day was so formative that she chose to make printmaking her focus in graduate school.

Hannah Diggs

Museum Associate in Curatorial Research